Over the past year, federal contractors have been subject to a continual and growing drum beat of regulatory measures seeking to alleviate concerns over data security and vulnerabilities in the information and communications technology (ICT) supply chain. For many, these measures had appeared as though they would crescendo with the rollout of the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) and the system-wide ban on covered Chinese equipment and sources stemming from the implementation of Section 889 of the 2019 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

Over the past year, federal contractors have been subject to a continual and growing drum beat of regulatory measures seeking to alleviate concerns over data security and vulnerabilities in the information and communications technology (ICT) supply chain. For many, these measures had appeared as though they would crescendo with the rollout of the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) and the system-wide ban on covered Chinese equipment and sources stemming from the implementation of Section 889 of the 2019 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

The coronavirus pandemic’s shift into a worldwide crisis has upended global supply chains, causing shortages in numerous critical industries - ranging from medical devices, personal protective equipment, and pharmaceuticals, to electronics and even the U.S. food supply. In response, public and private sector organizations have been compelled to focus not only on strengthening the resiliency of their supply chains, but also on improving their visibility into and understanding of the risks that they face. Amidst this backdrop, the government’s metaphorical regulatory drum has kept on beating and, to this point, has not been slowed by the pandemic.

In early April, DoD re-emphasized that the pandemic would not slow down the CMMC implementation. Just a few weeks later, the DHS Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s (CISA) Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM) Task Force released its “SCRM Essentials” guidance to help organizations demonstrate effective business governance over their vendor management practices. In mid-May, news outlets began to report that lawmakers on Capitol Hill were reviewing legislative proposals to incentivize companies to “re-shore” their manufacturing operations to the U.S.1 And, as of this writing, industry is awaiting rulemaking related to Part B of the Section 889 implementation. 2

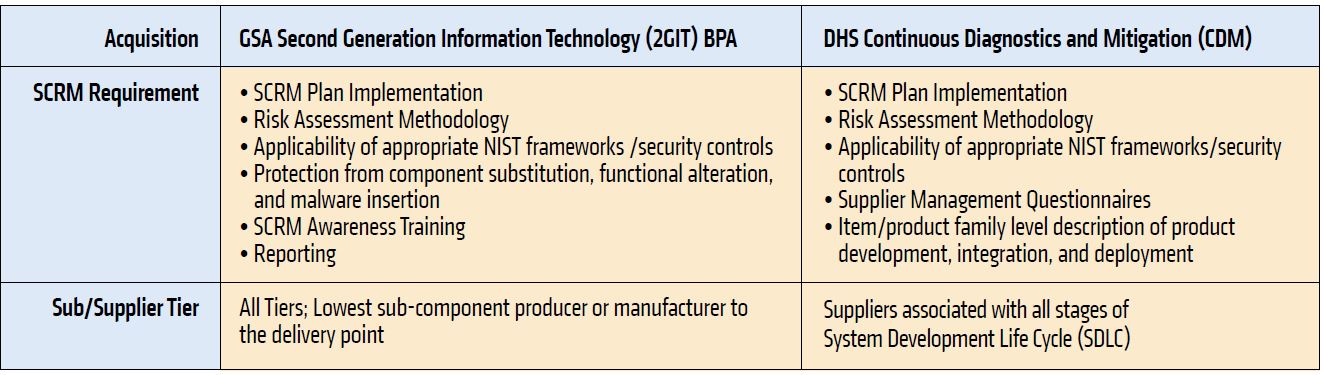

Given the persistent threat of foreign surveillance, it should not be a surprise that the federal government has pushed on with its efforts to secure and strengthen the federal supply chain. Notably, this underlying objective has also manifested itself in key acquisitions throughout the procurement landscape. Below is a sampling of SCRM requirements in two recent solicitations / programs that require plan development, implementation, and varying levels of assurance once contracts are awarded:

While these requirements may not be routine evaluation criteria in Federal procurements today, they offer a glimpse into how far they may reach when present. Given how critical it is to limit unsecure ICT operations within the federal supply chain and the absolute necessity to thrive in an environment of ever increasing technological threats, contractors should expect that SCRM requirements will become more prevalent in the future - especially where sensitive data is at play.

Several characteristics that contractors should take note of among these procurements, and others that we are aware of, include:

• Establishing a plan to provide transparency around how a vendor will identify, analyze, and manage risks among its subcontractors and supplier base;

• Identifying a plan of action to address security vulnerabilities as they arise;

• Use of supplier assessments to gauge risk throughout supplier tiers;

• Fulfillment of reporting obligations around SCRM practices; and,

• Testing to ensure conformance against the plan and solicitation requirements.

Understanding that a contractor positioned with a secure and strengthened supply chain will be extremely valuable to the Federal Government in the future, what tangible steps should contractors consider in the short term?

I. Evaluate Current Practices

To address ICT supply chain risk, contractors should at the very least consider the SCRM essentials. While a somewhat basic formulation, they do outline essential actions that all contractors can evaluate with their internal procurement and subcontract management teams to determine the effectiveness of their SCRM function. Of utmost importance, contractors should take steps to map their supply chain, to the furthest extent possible, to verify the chain of custody from raw materials, to assembly of sub-components, to the final product or application. This will also help an organization determine if there are any risky organizations in their supply chain, and also identify any areas where they may only have one supplier for a critical sub-component or item. By diversifying the organization’s sourcing of that particular item to multiple vendors, an organization can reduce the risk of a disruption should that vendor suffer from an event that would preclude them from delivering, or require remediation, exclusion, and reporting to the federal end user.

Additionally, by mapping their supply chain, contractors may be able to employ better management strategies across their supplier pool. These techniques are likely to vary by tier, as tier-one suppliers are likely to require a different kind of monitoring approach than those that are further down in the supplier ecosystem. More sophisticated and complex organizations should consider evaluating their SCRM practices to identify gaps. One option for assessing gaps is the NIST SP 800-161 (“Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Federal Information Systems and Organizations”) framework, which seeks to align people, process, policies, procedures, and systems, so that they can work in concert to address supply chain concerns.

II. Assess Vendors

A sophisticated SCRM function will require the completion of supplier risk assessments for risk rating assignment (for example, low, moderate, or high), and to provide visibility into the security culture of the third party vendor. Based on the level of risk and complexity of the relationship, contractors may need to develop short-term remediation plans with critical suppliers to bring them into compliance with contractor standards.

III. Update Policies and Procedures

The internal control environment for federal contractors has been an area of increased scrutiny in recent years. Formal documentation of SCRM-related policies and procedures supports the internal control framework, helps establish best-in-class practices, and ensures accountability and consistency so that processes are repeatable, systematic and integrated throughout the organization.

IV. Monitor and Evaluate

Once contractors put the necessary controls in place, they should continuously monitor their supply chain, working to identify changes or risks. Cross-functional involvement in the plan and communication across a variety of functional areas are likely to be an important component here. Technology can often be employed and serve as one component of many that will enable an organization to more efficiently identify changes and new risks as they arise. In addition to continuous monitoring of the supply chain, regular “health-checks,” or reviews of the SCRM plan, its policies and processes, and their effectiveness is considered a best practice.

Conclusion

Supply chain risk management has been receiving significant focus. For companies who do business with the federal government, even those that may be several tiers down in the supply chain, it is no longer something that is nice to have or that just makes good business sense; it is becoming a necessity. For some organizations, it can serve as a competitive advantage. Companies should not wait for these requirements to show up in a procurement or to be included as a contractual requirement; they should be proactive in addressing these risks. They should assess their supply chains now, and develop an SCRM plan that puts the systems, policies and processes in place that will allow them to better understand their supply chains and effectively mitigate and manage risks.

1 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-supply-chains-idUSKBN22U0FH. May 18, 2020.

2 Phase Two, slated to go into effect on August 13, 2020 is intended to prohibit the “use” of covered equipment, applications, and services by contractors. This means that the federal government will be prohibited from contracting with organizations that use banned items or services as a substantial or essential component of any system, or as critical technology as part of any system.

This article was published in the Summer 2020 edition of PSC's Service Contractor Magazine.